This idea must die: “Learning styles determine outcomes”

Professor Duncan Astle says an over-reliance on adapting teaching methods to specific individuals is misplaced.

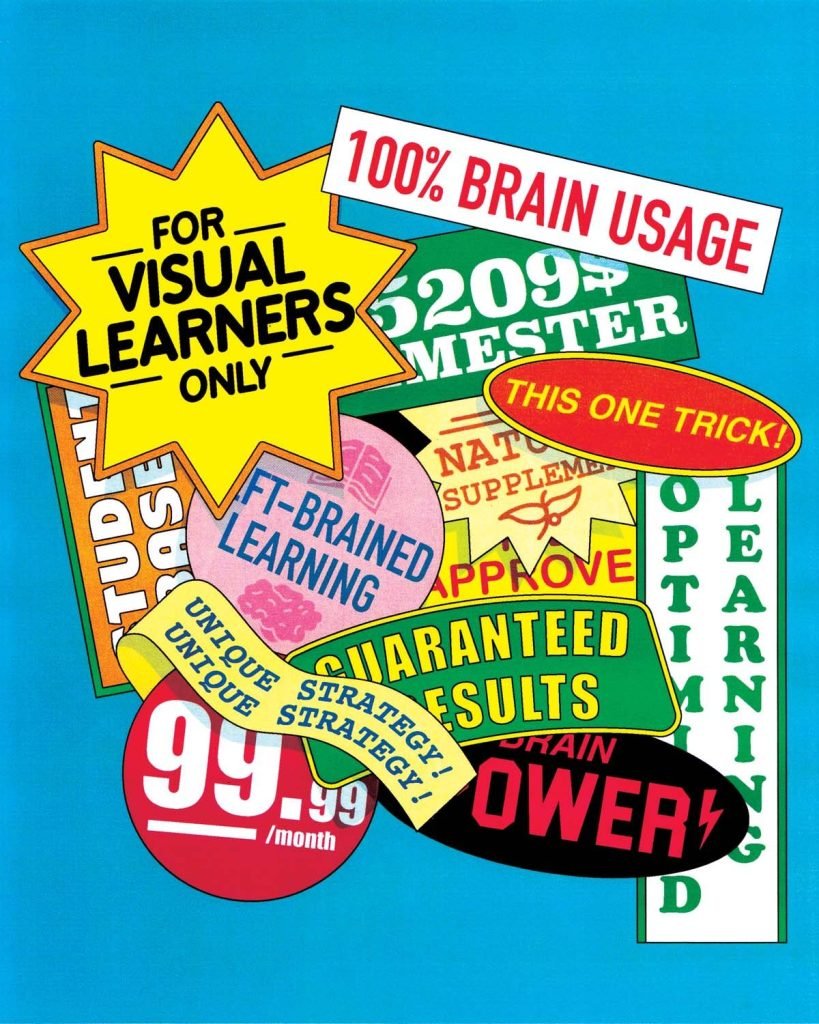

Visual, auditory, reading/writing and kinesthetic. The concept of learning styles has been with us since the late 1990s and early 2000s, when it was accepted that to optimise learning, teachers must identify the particular learning style of a child and align the way they presented information accordingly.

Only, it’s a myth. There is no evidence whatsoever to back it up. The idea has been extensively and empirically tested to see if children learn the most in conditions that align with their preferred ‘learning style’. They don’t. Yet a systematic review published in the journal Frontiers in 2020 found that teachers still believe they do. In fact, the review found that 89 per cent of teachers self-reported a belief in matching instruction to learning styles.

Why did this myth take hold? It was, of course, marketed extremely cleverly, and it is instantly understandable. There’s something appealing about dividing people into categories, like star signs. Plus, like many myths, something true is hidden inside it. That is the fact that children learn best in enriched, inclusive environments, in which the teacher thinks carefully about how they present a breadth of different materials and addresses key concepts from many different angles and perspectives. But it is nonsense to say that children are not learning because the ‘learning style’ doesn’t align with what the teacher is doing.

One might argue: ‘Even if this idea is bogus, is it really doing any damage?’ Well, firstly, these interventions are not always cheap, and those resources could be better used. I am reminded that around the same time as the concept of learning styles was growing in popularity, something called Brain Gym proliferated in schools: tools and techniques for teachers to use based on pseudo-neuroscience. Your left hemisphere is for logic, the reasoning went, and your right hemisphere is for emotion. You need to connect them by doing exercises that involve you using both halves of your body. Of course, to learn how to do this, a school must pay thousands every year for training, subscriptions and resources.

There is, however, a deeper problem with ineffective interventions. Say a child is struggling and is told to just watch videos, or do exercises, or take fish oils, or whatever the non-evidence-based intervention is – and it doesn’t work. What does that do to the child who has been told that this is the silver bullet for their difficulties? If a child is told they are a visual learner and the teacher starts delivering information that’s not in their preferred style, what’s the point in them paying attention? In short, bad interventions are not neutral, they can be counterproductive.

There is a broader issue here. Who gets to decide what counts as an effective intervention in an education setting? If you had a new drug, you’d take it to NICE, which has a very clearly laid-out pipeline and framework for deciding on the evidence threshold needed to roll something out nationwide. In education, there is no similar process. The Education Endowment Foundation has a good and useful website where they rate interventions based on evidence strength. But other than that, there is nothing.

Vast amounts of time and money are still invested in bogus interventions and frameworks

Teachers, meanwhile, have minimal resources and time, and are bombarded with new initiatives and ideas. They do not have the time to explore the evidence base. Teacher training would be a golden opportunity to carefully decide what it is worth teachers knowing about and investing their time in. But what goes into teacher training is usually determined by the university that’s running the PGCE course. There is no central agreement on what goes into teacher training – so it’s challenging to change.

A lot of the stuff we do in the lab is nerdy neuroscience, a long way from translation. But we want to help teachers in the classroom, too. So we also work from the teacher’s perspective. What do we know about the kinds of cognitive difficulties the children in their class might have? Or why some children might feel excluded from classroom learning? What can the teacher do to make sure that no child gets left behind? What barriers do children face in the classroom and how might teachers help to reduce those barriers? And how do our findings translate into easy-to-implement, cheap, and – vitally – evidence-backed interventions? If we really want to help our children, it is these aspects of learning we should be engaging with. Vast amounts of time and money are still invested in bogus interventions and frameworks. There must be a better way.

Professor Duncan Astle is Gnodde Goldman Sachs Professor of Neuroinformatics at the Department of Psychiatry and Fellow of Robinson College.

CAM

CAM