George Wylesol

This Idea Must Die: "Planting trees will solve climate crisis"

Professor Marc Macias-Fauria says tree planting at high latitudes will accelerate, not decelerate, global warming.

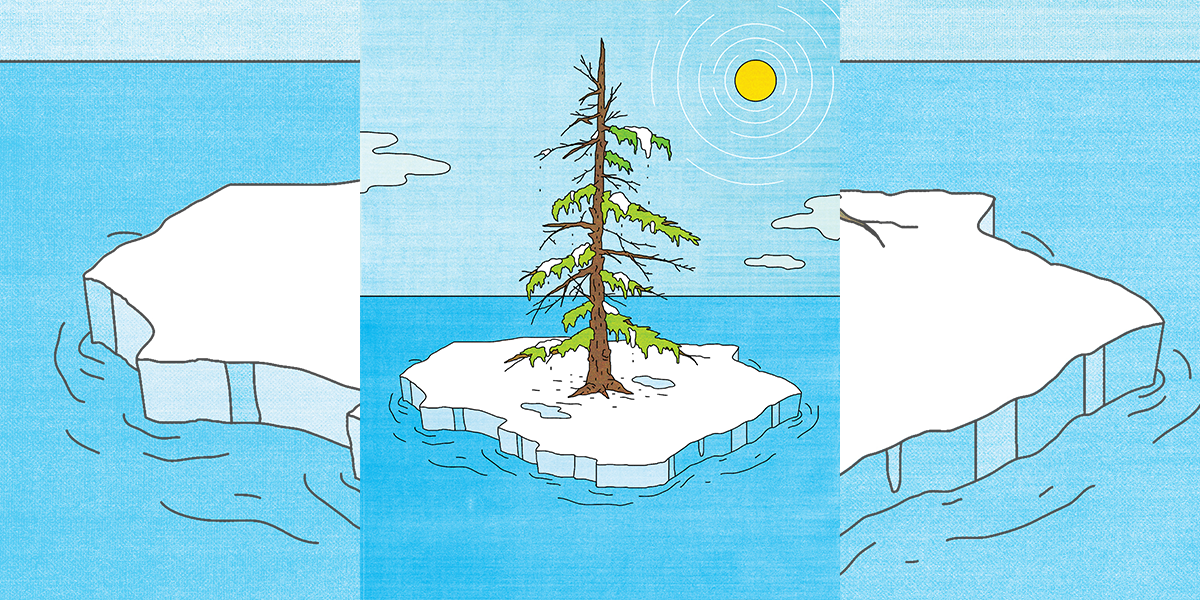

When it comes to planting trees to address the climate crisis, you can’t have your cake and eat it – and you can’t deceive the Earth. Tree planting is an important element in our attempt to address the carbon issue, but only if it’s done in the right places. And while the temptation to take advantage of a warmer climate by pushing further and further north with reforestation is strong, it is not the answer. Take the Arctic. The tundra area is defined as treeless, but with global warming – and especially Arctic warming, which is heating faster than the rest of the planet – it is now possible to grow trees in the north. This is already happening in several places, with afforestation and reforestation initiatives in Greenland, Iceland and Alaska.

Planting trees darkens the surface of the Arctic, lowering its overall albedo; the result is more energy remains trapped in the Earth’s atmosphere

Needless to say, people living in these areas have the right to plant trees – for economic reasons, for example, such as wanting to reduce reliance on timber imports – but they cannot claim that planting trees will mitigate climate change, because the opposite happens.

As we argue in our recent paper, led in collaboration with the University of Århus, and with the participation of several researchers from boreal and arctic institutions, planting trees in the Arctic will harm the planet. That’s because tree plantations in the high latitudes are modifying the ‘albedo’ of the surface of the Earth. The albedo is the amount of energy from the sun that is immediately reflected back into space. The Arctic has a lot of snow and no trees, which means that the surface is relatively smooth and very reflective, and up to 90 per cent of the sun’s rays are sent straight back into space instead of being absorbed on Earth. If you plant trees, these darken the surface of the Arctic and lower its overall albedo, so less energy is bounced back. Instead, it is trapped on the Earth’s surface and in the atmosphere, contributing to global warming.

The overall negative effect on the albedo is greater than the carbon sequestered by the trees, so it doesn’t solve anything. It’s like taking medicine for a headache that causes more headaches. Another parameter is that the Arctic is not characterised by storing carbon in plants above ground but in the soil, which is really rich in carbon. There is more carbon in the soil of the Arctic than in all living plants on Earth. This soil is already starting to decompose as the planet gets warmer, and when it is disturbed it enhances the emission of stored carbon. No matter how careful the reforestation programme, it is inevitable that it will disturb the soil and release even more carbon into the atmosphere.

Keeping these landscapes open is a better option than turning them into forest. That supports the albedo, and it is also good for the large animals that live in the Arctic and provide food and other resources (such as fur and skins) for its indigenous populations. There is ample evidence that large herbivores affect plant communities and snow conditions in ways that result in net cooling. The final problem is that if you plant trees in the Arctic they tend to die. There are a lot of fires and natural disturbances in the Arctic, so trees are very vulnerable and only last a few decades – not long enough to counter the negative impact from the carbon in the soil or the impact on the albedo.

Albedo, carbon release, securing traditional species and local communities: key factors when it comes to tree planting. Done thoughtfully, there are obvious benefits to successfully managing our climate challenges. But done wrong – or in the wrong places, such as the Arctic – it is not the solution, and will have the opposite effect.

Professor Marc Macias-Fauria is Professor of Physical Geography at the Scott Polar Research Institute.

CAM

CAM