What happens when all your BFFs are more URL than IRL?

The parasocial relationship – a one-sided friendship, typically focused on a celebrity – is not new, but it has recently become turbo-charged. Should we be worried?

“Imagine a celebrity or a politician you greatly admire does something you consider deeply immoral and repugnant. Would you stand by them?” That was the question posed by Simon Karg, co-author of a study around our willingness to update our beliefs about those we support – with some surprising results.

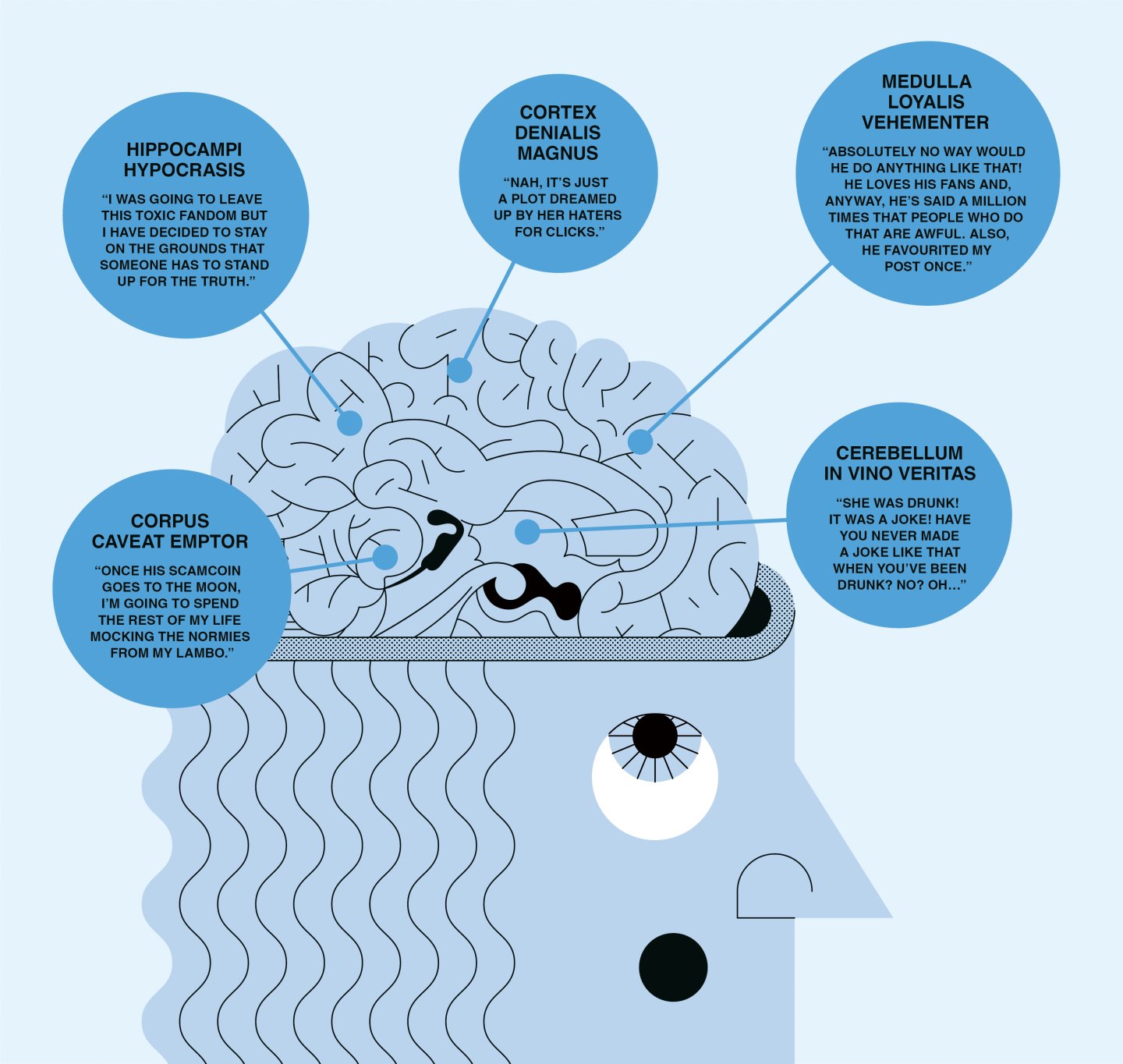

“We can see that people often keep holding on to a positive character evaluation even when the admired person commits a severe transgression,” says Karg, then of the Cambridge Body, Mind and Behaviour Laboratory. “The more important the person has been to us, the less likely we are willing to change our favourable opinion.”

Along with Michelle Lim (Churchill 2015) and Professor Simone Schnall, Karg analysed posts from thousands of social media users either side of a scandal involving YouTube celebrity Logan Paul in 2018. Paul and friends had filmed the dead body of a man in Japan’s Aokigahara forest – tragically known as a ‘suicide site’ – and shared it with his followers online, complete with highly inappropriate commentary.

Following the video, and despite a public apology, Paul faced a barrage of criticism, a YouTube ban, and lost several lucrative sponsorship deals. But his massive fanbase of 15 million YouTube subscribers – the ‘Logang’ – furiously defended him. In fact, analysis of 36,464 posts from Paul’s followers found that three-quarters of the YouTube users who had left comments on a Logan Paul video before the scandal continued to support him afterwards. Just 16% expressed anger at the video, and only 4% disgust. Six years later, Paul has more than 23 million subscribers, and many vastly more lucrative sponsorship deals.

It’s a fascinating snippet of the power of the parasocial: the intense relationships we have with people who don’t know we exist. Of course, these relationships are nothing new. [Here’s Alfred, Lord Tennyson (Trinity 1827) on Lord Byron’s (Trinity 1805) death, “I was fourteen when I heard of his death. It seemed an awful calamity; I remember I rushed out of doors, sat down by myself, shouted aloud, and wrote on the sandstone: BYRON IS DEAD!”] But back in preinternet days, we were used to admiring from a distance. Now, we can see everything.

And that, of course, comes with a major health warning. While for most of us, parasocial relationships are entirely passive – we know Taylor Swift isn’t really our friend – for others, they can be extraordinarily intense, for both the admirers and for the object of their attention. Take Ibrahim Mohammed (Wolfson 2016), whose connections with online subscribers became more extreme than he could ever have imagined.

When Mohammed wanted to apply for Cambridge from his secondary school in East London, he couldn’t find the sort of real-life insights into Cambridge life he was after. So in the Lent term of his first year, he started making YouTube videos about his life at Cambridge. “It blew up overnight, and just kept growing and growing over the next three years,” he remembers. Although he no longer makes new content for his channel, it still has 134,000 subscribers – and his 131 videos, covering everything from how Cambridge students get motivated to discrimination against poor students, have a total of nearly 14 million views.

The comments under his videos are intensely personal. ‘I had a 10-hour shift today and I came home so tired and upset. You made today better for me, thank you,’ says one. And they weren’t just online, as Mohammed describes: “I got stopped on the street and at University events by people who were crying, saying how much the videos had helped them.” He soon found himself working directly with the Cambridge communications team. “When they contacted me, I thought it was going to be about trying to shut me down. But it turned into an amazing collaboration.”

Yet he found that parasocial relationships can have a darker side. “It was difficult when people started to see me as a friend and felt that they could open up about safeguarding issues. I had messages saying: ‘Ibz, I need your help, I’m homeless, I’m stressed, I’m going to kill myself.’” He was given support by the University’s safeguarding and mental health experts, who provided him with responses and resources.

Mohammed never saw this unexpected responsibility as a burden. “Absolutely not. I always saw it as a privilege and an honour, because I was doing it for my community.” And he was determined to create something tangible. “I wanted to fund scholarships for some of the most deprived students in the UK, and I’m incredibly proud of the role I played setting up the Aziz Foundation’s Cambridge scholarships, for example. We currently have two students at Wolfson – and one of them used to watch me on YouTube. How crazy is that? And I felt that this person really shone in the interview because it was like he already knew me, so he didn’t need to be nervous.”

“Social media allows you to set up independent communities to idolise,” says Lim, co-author of the Logan Paul research, which won the prestigious Soloman Asch Prize in 2023. “Plus, there’s the echo chamber factor. It’s commonly seen in psychology that the more you are exposed to something, the more you like it – even if that exposure isn’t necessarily positive or negative. These three drivers all increase the intensity of parasocial relationships. I don’t know whether social media was designed to do this, or whether it’s an unintended consequence.”

Lim now works in the Human-Machine Understanding capability at Cambridge Consultants. “Algorithms will look at your preferences and push relevant content about that person towards you. That won’t just be content created directly by your parasocial friend, but also the community around them. And that, in turn, reinforces the parasocial relationship.”

Ruby Cline (Murray Edwards 2021) has also experienced both the highs and the lows of parasocial relationships. She started creating content on short-form video social media site TikTok when she moved to a new school for sixth form. “Lots of my fellow students had parents who didn’t speak English. Some were already juggling school and two or three jobs to support their families, and didn’t have the luxury of lots of time.” So, she started by creating short videos on political education to help, and then branched out into general knowledge.

At the beginning, when her “very small” account had between 5,000 and 10,000 followers, the relationship she had with those followers seemed more social than parasocial: she knew their names, their ages, their likes and dislikes. “They seemed like very deep, genuine social relationships. But I also recognise that they knew a lot more about me than I knew about them. And as my follower count grew, it became a lot less personal. Now that I’ve got videos that are getting hundreds of thousands – or even millions of views, I have no idea who those people are.”

I get people who seem to know me well and really dislike me, in a way that seems disproportionate to the relationship they should be able to have. What I find interesting is that people follow me, watch all my content, and then tell me that I’m an infuriating bitch.

The relationship between Cline and some of her followers is very different from Mohammed’s, she says. “I’ve come in wielding opinions. I get people who seem to know me well and really dislike me, in a way that seems disproportionate to the relationship they should be able to have with someone on the internet. Part of it comes from being a woman on the internet who has opinions. But what I find interesting is that people follow me, watch all my content, and then tell me that I am an infuriating bitch.”

It’s easy to see why you’d feel deeply connected to someone you love – but why spend so much time with someone you hate? There’s a theory for that, says Schnall, Director of the Body, Mind and Behaviour Laboratory. “Psychologist Robin Dunbar’s social brain hypothesis proposes that the reasons humans have such large brains is that they have to keep track of social relationships. That means monitoring other people to decide if they are a friend or foe. And that means talking about them and gossiping about them. Dunbar says that it could even be that language evolved for that very purpose: gossiping about other people.”

Yet could we be losing the ability to have real relationships? Schnall says that there will inevitably be a trade-off, but, she points out that, unlike real-life relationships, parasocial relationships are safe. “You don’t get any positives back. But you also don’t get any negatives. Your parasocial relationship can’t reject you or criticise you. It can’t turn sour. There is no cost, and no risk.”

Watching how the parasocial morphs and changes in the future will be fascinating, says Lim. And as the endless, random carnival of videos, reels, stories, posts, images and vlogs we are fed becomes bigger, faster and more disposable, it’s hardly surprising that Cline believes the golden age of digital parasocial relationships – as exemplified by the ‘Logang’ – is coming to an end.

“Today, people don’t see content creators as friends,” she says. “They use them so they can shop this, buy that, and integrate it into their lifestyles – but those lifestyles will always be a poor imitation of the ones people are paid to create. And those creators are just thrown away – there’s a hundred others like them, after all,” she says.

But in the end, Mohammed points out, the best parasocial relationships grow when someone has seen, heard or read something they like, “and that’s usually a good thing,” he says. “I think it’s cool to have some form of escapism – as long as it’s healthy.”

CAM

CAM