Akan ‘mmbramm’ goldweights

Among the great cultures of sub-Saharan West Africa were the Akan – a linguistic group comprising many different tribes and ethnic groups of present south-western Ghana and south-eastern Côte d’Ivoire. Over centuries, the Akan mined gold, and sold it on vast trading routes across the Sahara Desert. From the 1400s, they developed a system of ‘mmbramm’, or goldweights, to measure gold dust, the Akan currency. These weights (above) were collected by the Ghanaian anthropologist Dr Alexander Atta Yaw Kyerematen. He appears to have given them, along with three others, to Mary Cra’ster, an assistant at the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in the 1970s, during a research trip to Cambridge. Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge

Black Atlantic

How does Cambridge fit into the mesh of money, people and culture created by the transatlantic slave trade? A new research project is making discoveries about the objects in its collections, the people who collected them and how their stories connect Cambridge to a global history of colonialism.

Many an exhibition aspires to be the last word on its subject, to offer the ‘definitive’ assemblage of objects or interpretation. But at the Fitzwilliam, the creators of one exhibition insist it is merely the first word, an opening conversation, in a massive, multi-year research project. In fact, Black Atlantic: Power, People, Resistance may be the most ambitious undertaking in the combined histories of the University of Cambridge Museums. That’s because in exploring its subject, it also explores, reconsiders and aims to reshape the very role and purpose of museums and collections.

“It’s been three years of research and thinking to get to this point,” says lead curator, historian Jake Subryan Richards (Caius 2010). “And from the beginning, the museums were clear this would be part of a longer process of transformation and change. As an expert on the African diaspora and the history of transatlantic slavery, my role was to come up with a research agenda and work alongside curators. We began with a single question: ‘How far, and in what ways, did transatlantic slavery and empire shape the collection and museums of the University?’ There’s a unique range of institutions here, covering historical and contemporary fine art; archaeology and anthropology; the history of science; zoology, botany and earth sciences; as well as the applied arts. They have some five million objects in total in their collections, so this is only the first dive in.”

“Under what circumstances did our collections arise? How did objects get here: was it a fair exchange; or via a purchase, loan or bequest; or was it via seizure?” asks Victoria Avery, Keeper of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts at the Fitzwilliam, who partners Richards as co-curator of Black Atlantic, and is already working on a follow-up exhibition, due February 2025. “Where did the money come from that enabled a museum to be built and its holdings to be accumulated? If we’re talking about a zoological or botanical specimen, or a mineral sample, who was responsible for its collection, and have they been properly credited? The University of Cambridge museums consortium wanted to organise a series of iterative exhibitions and displays with associated public programmes to answer some of these questions and do some long overdue collection reckoning. Black Atlantic is just the first milestone in this long journey of institutional change.”

Black Atlantic explores the creation and transmission of cultures by people of the African diaspora as they confronted Atlantic enslavement and empire and their pernicious afterlives

“We intentionally go beyond Cambridge, and beyond Britain,” says Richards. “We wanted to show how collections here are related to places across the Atlantic world – on display are items from Ghana, Suriname, Brazil and more.” The exhibition’s title makes this scope clear. ‘Black Atlantic’ as a concept refers to “the creation and transmission of cultures by people of the African diaspora as they confronted Atlantic enslavement and empire and their pernicious afterlives”, states the exhibition’s accompanying publication – itself no mere catalogue of exhibits, but a powerful treatise that at times reads like a manifesto for reimagining how we think about material culture and our relationship to it.

Not all visitors will find it easy to engage with the ideas Black Atlantic explores. But encouraging that engagement is a task to which the curators and the many individuals, institutions and organisations consulted are fiercely committed. “Many British people have been taught history in a particular way, but we have to rethink a lot of the assumptions we may have been taught and move on from the dominant cultural perspective to include stories and perspectives that have been historically marginalised and left untold.”

We have to rethink a lot of the assumptions we may have been taught and move on from the dominant cultural perspective

Consideration of how these histories will impact visitors has been painstakingly built into the exhibition experience, thanks partly to Wanja Kimani, a visual artist and the third member of the lead curatorial team. “Some of the historic material included is racist and problematic,” says Kimani. This includes objects such as a pseudoscientific ‘Table of coloures’, or a pair of sculptures of young Black men wearing racist fantastical African clothing, both from the 17th century, or the deck-plan of an 18th-century slave ship. “For myself as a black person thinking about a black audience, I wanted to instil care by having these objects in conversation with artists active now,” Kimani explains, “looking at how contemporary artists are responding to and engaging with the themes these objects embody.”

That thematic structure, and the exhibit selection of Black Atlantic, proved a mammoth undertaking. From those five million objects in the nine consortium institutions’ inventories, a shortlist was assembled. “Then from around 1,000 items, we had to get it down close to 100,” says Richards. “Every few months we’d have a big pin-up meeting where we’d move images of objects around on a board, discussing key themes and object groupings with external advisers and within the Fitzwilliam.”

This is the start of a conversation. It’s about what institutions like the University of Cambridge Museums are for. We hope everyone who visits will join this conversation

“It was a massive puzzle we were trying to piece together,” says Kimani. “We had to think about how we would divide the exhibition sections, what stories we’d keep, all while looking at the overall picture.”

One insight from that process was that omissions in collections can speak as significantly as acquisitions. “We discovered we had a number of significant gaps in our historic collections, including works by Black artists, which is symptomatic of imperialist collecting policies, in which certain types of objects or makers were considered important and worth collecting while others were not,” says Avery. As a result, Black Atlantic also includes several loaned-in but potent exhibits. Borrowed from London’s Linnean Society, for example, is an immaculate late 18th-/ early 19th-century botanical illustration of a breadfruit tree that unusually features a human figure – of an enslaved man, but depicted at rest in a heroic pose and with great care – from the hand of John Tyley, an artist of African descent who boldly signed several of his pieces, laying claim to his artistry.

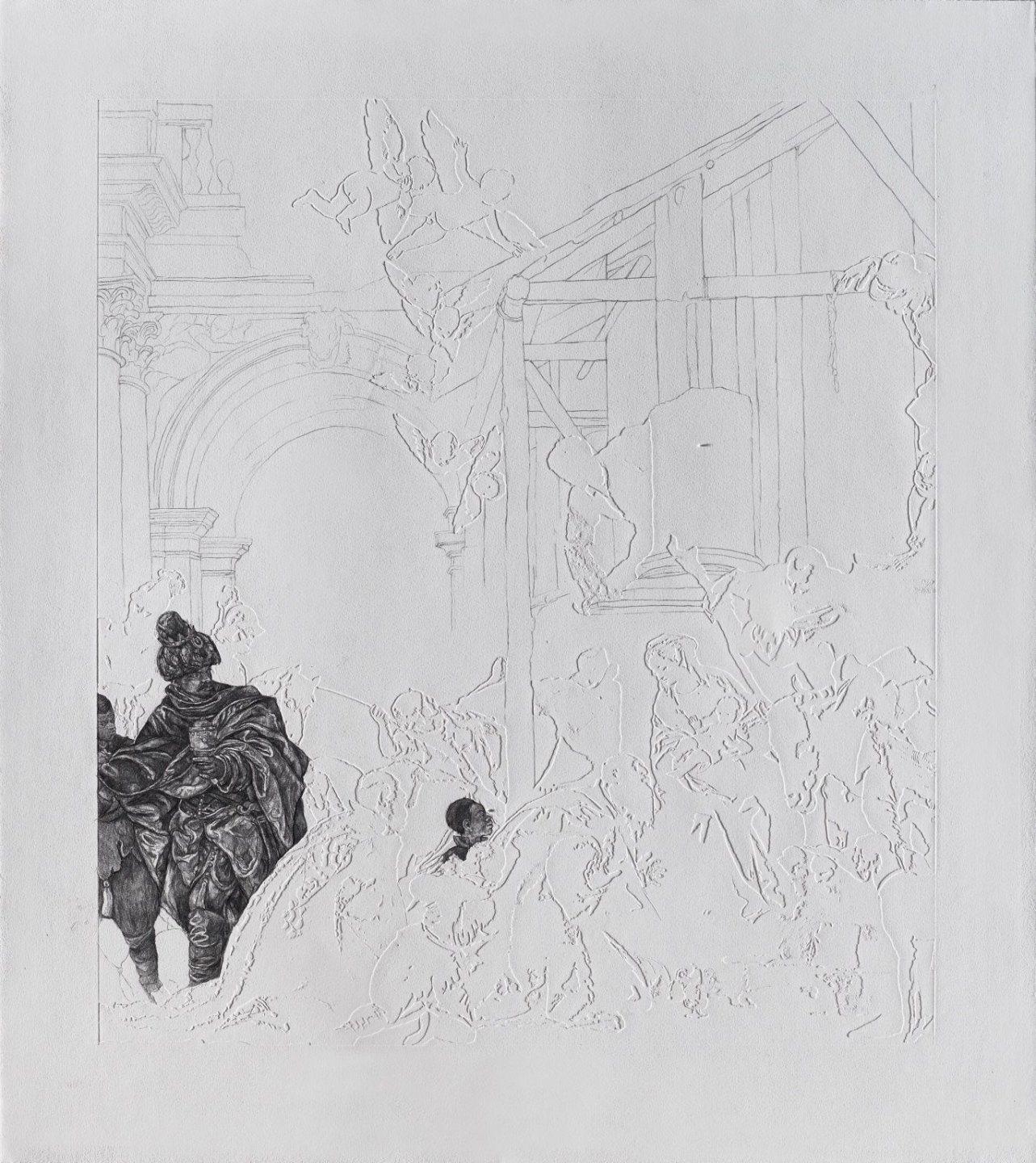

Vanishing Point by Barbara Walker

How do you represent erasure? Barbara Walker’s Vanishing Point series derives, in part, from her childhood encounters with art in public museums and galleries, which were notable for the absence of Black people. “I looked at Old Master paintings and prints to see how the Black subject is represented within the Western canon,” says Walker. “A lot of viewers don’t even see the Black figures in the original paintings. The conversations are about perspective, composition and colour, but the Black figure is rarely discussed. I find that problematic. The Vanishing Point series asks how do we move on from this? I use erasure as a metaphor for how the Black community is overlooked, ignored and even dehumanised by society.” Through blind embossing, Walker erases the dominant white figures present in the original compositions and emphasises the Black subjects by drawing them in fine detail using graphite onto the now blank sheet of white paper. The resulting artworks thus focus exclusively on the Black figures, making them the subjects rather than the objects and appendages to the white figures of the original. Vanishing Point 17 (Veronese), Barbara Walker, Cristea Roberts Gallery, London

“Another loan that felt essential to the exhibition is Jan Mostaert’s brilliant painting from c.1525-30 of a yet-to-be identified Black man, which the Rijksmuseum believes is the earliest known portrait in Western art of an identifiable Black person to survive,” says Avery. “It’s from a time before the rise of Atlantic enslavement and shows how Black subjects were painted with equal dignity, respect and brilliance as their white counterparts. It shows us what was once the norm, and what should have remained so had it not been for the rise of slavery and anti-Black racism – an alternative history.”

Contemporary works offer counterpoints to the often degrading or marginalised depictions of Black people that have come down through history as it really played out, in which, across centuries, European empires transported an estimated 12.5 million people from Africa to colonies in the Americas. Barbara Walker, for example, creates dazzling reversions of works by great masters such as Veronese and Titian, in which Black subjects populate the background and margins as onlookers or attendants. In her Vanishing Point and Marking the Moment series, the putative subjects are defocused – greyed out, or merely embossed – while the Black figures are fully etched, given compelling presence. “There’s something very poetic about Walker’s work,” says Kimani. “It’s quiet, but it’s also screaming at you. She balances absence and presence. Black Atlantic displays many objects that were collected by black people who were never credited, but Walker is saying: ‘We’re here; we always have been.’

Who gets remembered and why?

These paintings show people connected by the history that created the Black Atlantic, and were made in England in the 18th century. The name of the Black man has been lost or was never recorded. An outdated interpretation suggested he was Olaudah Equiano (c.1745-1797), a prominent writer and abolitionist who got married and lived in Cambridgeshire towards the end of his life. But the fact that after decades of research his identity still remains unknown highlights the ways in which the dominant culture in Britain has failed to record Black sitters’ identities and histories. The name of the white man is Richard Fitzwilliam, future 7th Viscount (1745-1816). At his death, Fitzwilliam bequeathed the enormous sum of £100,000 together with his substantial library and art collection to the University of Cambridge, where he had studied. At the time, the fact that Fitzwilliam’s riches came from a grandfather made wealthy in part by the transatlantic trade in enslaved African people was not deemed problematic. Portrait of a Man in a Red Suit, Unknown artist Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery, Exeter City Council. Portrait of The Hon. Richard Fitzwilliam, Joseph Wright of Derby The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

“It’s important that contemporary artists aren’t carrying all the burden of pushing back on problematic histories,” Kimani says, “and my approach to curating in this instance was not to put it all on their shoulders. But having contemporary work in this space, in the Founder’s Gallery, says a lot. The inclusion of contemporary work shows the potential of the future these artists are creating.” As Kimani suggests, the location of the current exhibition – the Founder’s Gallery of the Fitzwilliam – is one of the most potent choices of all. For as is now recognised, and revealed in further detail by Richards’ new research, the very existence of the museum was made possible by the slavery-derived riches of its founder, the 7th Viscount Fitzwilliam (shown above). His Anglo-Dutch merchant grandfather had been director of the South Sea Company and the Royal African Company, and bequeathed Fitzwilliam both vast wealth and his art collection, while the viscount further acquired annuities in the restructured slave-trading company. All then passed to the University so that, as Fitzwilliam’s 1816 will states, it might build “a good, substantial and convenient Museum, Repository or other Building” for preserving and expanding the collection.

“Black Atlantic is a story of empires in dialogue with each other, among them the British and Dutch world of Fitzwilliam and his grandfather,” says Richards. “But we are also thinking carefully about how that top-down story of expansion is connected to bottom-up experiences, to the places that oppressed people negotiated in the spaces between empire, where they made their own forms of free community.

“We end the exhibition by saying: ‘This is the start of a conversation.’ It’s about what institutions like the University of Cambridge Museums are for. We hope everyone who visits will join this conversation.”

Black Atlantic: Power, People, Resistance, the first in a series of exhibitions, is at the Fitzwilliam Museum until 7 January 2024. The Fitzwilliam’s exhibitions, research, conservation, learning programmes, public engagement and acquisitions are made possible through acts of generosity. To find out how you can get involved, contact Claire Alfrey at claire.alfrey@admin.cam.ac.uk

CAM

CAM