Campendium: Lent Term 2024

Philanthropy

£56m raised so far to build the new Cambridge Children’s Hospital – halfway to the £100m target.

Academic rankings

Cambridge academics ranked among the top female scientists in the world

Twelve Cambridge academics have been ranked among the top female scientists in the world – one of whom is also ranked first in Europe.

Kay-Tee Khaw, Emeritus Professor in Gerontology and a Gonville and Caius Fellow, was placed fifth worldwide and top in Europe, according to Research.com’s Best Female Scientists in the World 2023 rankings. Her study on how differences in lifestyle are associated with better life expectancy informed the ‘Small changes, big difference’ campaign in 2006.

Barbara Sahakian, Professor of Clinical Neuropsychology in the Department of Psychiatry, and a Fellow of Clare Hall, was placed sixth in the UK. Her recent research includes a study showing how reading for pleasure when young can boost mental health and cognitive performance.

Joining Professor Khaw and Professor Sahakian in the UK top 10 is Carol Brayne, Professor of Public Health Medicine in the Department of Psychiatry and Fellow of Darwin. She was awarded a CBE in 2017 for services to public health medicine and has pioneered the study of dementia.

Nine further female Cambridge scientists made the rankings, which are based on an analysis of more than 166,000 scientist profiles.

Imed Bouchrika, co-founder of Research.com, says that the purpose of the ranking was “to recognise the efforts of every female scientist who has made the courageous decision to pursue opportunities despite barriers. Their unwavering determination in the face of difficulties serves as a source of motivation for all young women and girls who pursue careers in science.”

Research Deconstructed

Wild honeyguide birds communicate with humans to help find honey

A new study has found that wild honeyguide birds in Tanzania and Mozambique prefer to team up with local human honey-hunters to find wild bees’ nests.

Honeyguides and humans use specialised sounds to communicate with each other – increasing their chances of finding honey and beeswax.

And while human honey-hunters in different parts of Africa use different calls, the birds studied showed a distinct preference for their local partner’s calls.

Co-lead researcher Dr Claire Spottiswoode works closely with the Yao and Hadza communities, whose guidance the team has relied on for more than a decade.

Three-minute Tripos

Drought was behind the rise of skateboarding in 1970s California. Discuss.

Dude, it’s hot. Real hot.

I get you, dude.

Like, it’s so hot, I ain’t gonna fill my backyard swimming pool.

You don’t have one, dude.

But if I did, then I’d keep it empty, so I could do some rad 360s, acid drops or Casper flips.

I don’t know what those are, dude.

That’s because you’re not a skater in 1970s Ca-li-for-ny-ay, dude.

Neither are you, dude.

But if I was, dude, then I’d tell you how it was only the extreme drought conditions of the 1970s that made skateboarding possible.

I think you’ll find it was a tad more complex than that, dude.

How so, dude?

This heavy new study shows that beyond the drought, it was, like, the entanglement of environmental, economic and technological factors that led to the explosive rise of professional skateboarding culture in the 1970s.

Woah.

I know, right?

Like what entanglements?

Like new technology, like polyurethane making wheels grip better… Like Cali’s entrepreneurial culture and the rise of the hand-held video camera…

Like, it could never have happened at any time except, like, then. The only ‘then’ in the history of, like, ever.

Like this lead dude author Professor Ulf Büntgen from Cambridge’s Department of Geography says: “These developments are not random – in the case of skateboarding, you needed each one of the ingredients to exist in the same place and time. It couldn’t have happened 10 years earlier, 10 years later, or a few hundred miles away.”

Cool, dude.

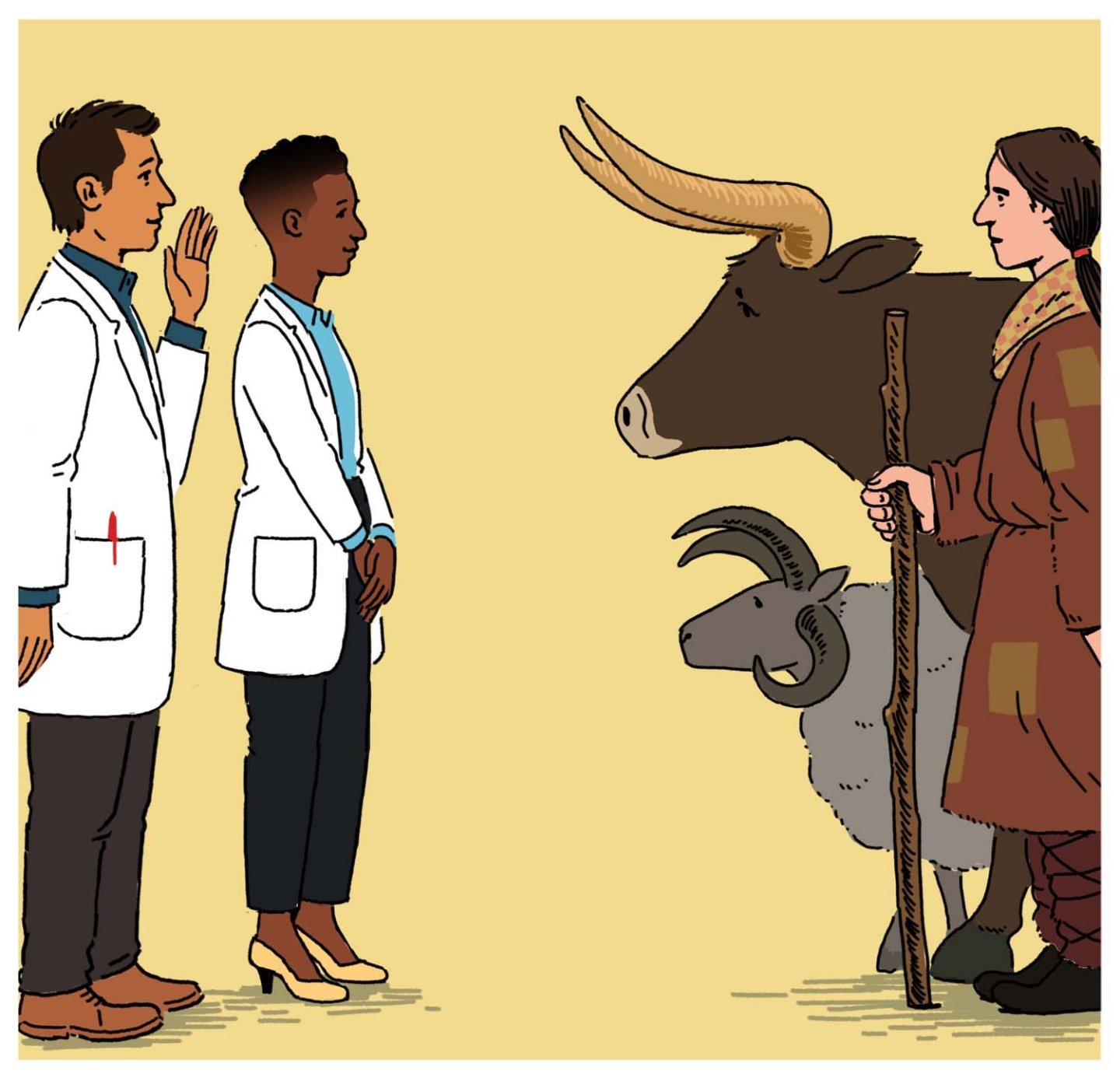

Research

Ancient DNA clue to diseases origins

Researchers have revealed the origins of neurodegenerative diseases – including multiple sclerosis (MS) and Alzheimer’s – by sequencing ancient human DNA.

The international team, co-led by Professor Eske Willerslev at the Department of Zoology, studied the bones and teeth of almost 5,000 humans living in western Europe and Asia up to 34,000 years ago. By comparing ancient DNA to modern-day samples, the team mapped the spread of genes and diseases over time.

The study found that the genes which significantly increase a person’s risk of MS were introduced into north-western Europe around 5,000 years ago, by sheep and cattle herders known as the Yamnaya people, migrating from the east.

These genetic variants protected them from catching diseases from sheep and cattle, but also increased the risk of developing MS. The findings explain why there are around twice as many modern-day cases of MS in northern Europe than southern Europe: the Yamnayas are thought to be the ancestors of many people in north-western Europe.

“These results change our view of the causes of MS and have implications for the way it is treated,” says Professor Willerslev.

Pregnancy sickness breakthrough

A Cambridge-led study has shown for the first time why many women experience nausea and vomiting during pregnancy – the culprit is a hormone known as GDF15, produced by the foetus. This discovery points to a potential new treatment: exposing women to the hormone before pregnancy to build up their resilience.

In brief

A new look at history

In a challenge to our understanding of Roman history, a Cambridge-led team of archaeologists has found that Interamna Lirenas in central Italy bucked Italy’s decline in the 3rd century AD. “We’re not saying that this town was special: it’s far more exciting than that,” says author Dr Alessandro Launaro.

Parental bonds

A loving bond between parents and their offspring early in life increases a child’s tendency to be ‘prosocial’, kind and empathetic, says research from Ioannis Katsantonis and Dr Ros McLellan in the Faculty of Education – emphasising how powerful early parenting can be.

French letters

Professor Renaud Morieux’s study of more than 100 letters sent to French sailors by their fiancées, wives, parents and siblings reveals rare and moving insights into the lives, loves and family quarrels of everyone from peasants to officers’ wives. The documents, now held at the National Archives, were confiscated by the Admiralty 265 years ago and never opened – until now, that is.

CAM

CAM