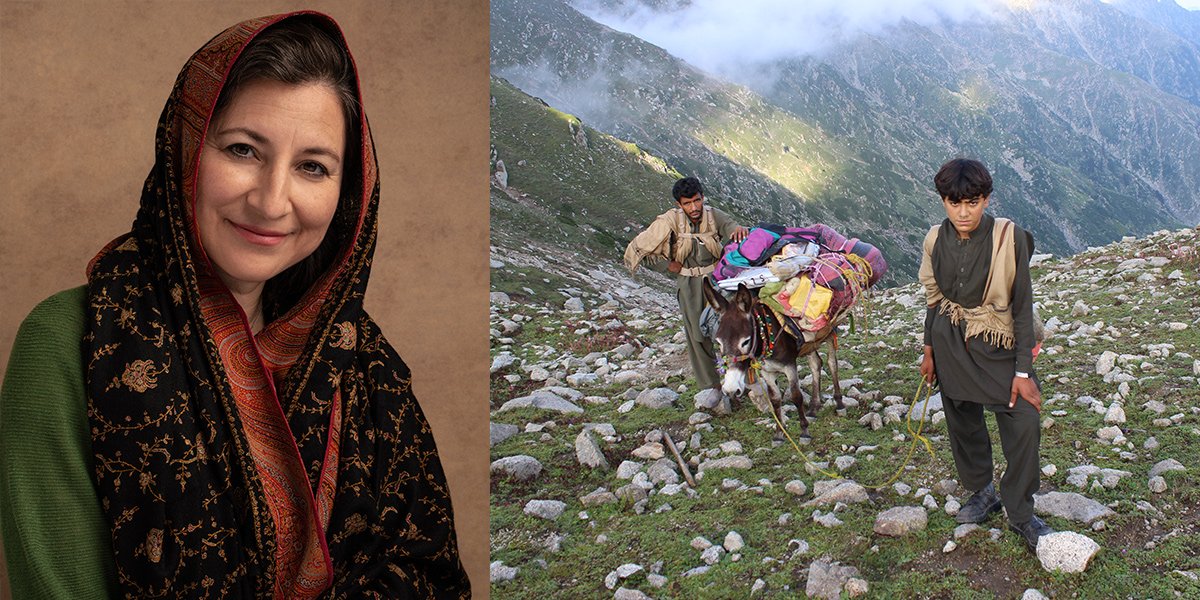

A blueprint for world peace – Dr Amineh Hoti

Dr Amineh Hoti (Lucy Cavendish 1995) has developed peacebuilding initiatives in the UK and across the world. Amineh's programmes transcend disciplines to help communities from different faiths understand each other and live more harmoniously.

Cambridge has been a home for me, both literally and intellectually.

Dr Amineh Hoti

Amineh's courses have helped change the mindset of young people from remote regions, including those from the border of Afghanistan and Pakistan. In her writing, Amineh has contributed valuable chapters for books on the Pope, the former Chief Rabbi and in UNESCO publications.

But Amineh’s path has not been easy. She has had to battle misogyny, cultural stereotypes, Islamophobia, and most recently, cancer, from which she has since recovered.

Early in life, Amineh faced down harsh resistance: “I was told not to study, not to work, not to engage in public debates,” she says. “But my father, a peacebuilding ambassador, stood by me and always encouraged me. I eventually found my voice as an international public intellectual with a base in Cambridge.”

A woman from Swat

"My first school was under a tree, in northern Pakistan,” says Amineh. “My father, Professor Akbar Ahmed, was a renowned anthropologist and civil servant. He always wanted me to study. But when he was posted to Waziristan, we found that there were no school buildings there. So, my little brother and I would sit with the other children – on the ground, under the shade, slates in our hands.”

Amineh is from Swat, a beautiful alpine area of Pakistan with a fraught recent history. From 2007 to 2009, it was under the military occupancy of the Taliban. Amineh’s connection to this part of the world goes back much further: she is the great-granddaughter of the King [Wali] of Swat, who set up the region’s first university.

“He also opened Swat’s first girls’ schools in the 1920s.”

Much later, when her great-grandfather had passed away, the Taliban destroyed these girls’ schools after taking control of the region.

But during the Wali’s period, education had thrived. It was a time when many prominent people visited Swat. On one occasion, Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh were the Wali of Swat’s personal guests. Her Majesty described Swat as ‘The Switzerland of the East.’

Swat has always hosted people from many faiths, including Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam, as well as a wide range of tribal groups. But when studying anthropology at the London School of Economics, Amineh came across a jarring representation of her people. She vividly remembers picking up a book and reading about her homeland as seen through the lens of visiting anthropologists.

“The women were described as ghost-like, marginal and secondary. It was a strange picture of Swat that I was not familiar with. The people I knew, women included, were vibrant, spirited and essential to the running of their communities. Reading that inaccurate description of a society I knew so well, I thought how amazing it would be to go back to Swat and bring out the voices of the women there and record their perspectives first-hand.”

Later in her degree, Amineh learnt more about some of the founding fathers of anthropology. They were eminent professors who’d forged a discipline she loved, but who also described indigenous people like those from Papua New Guinea as ‘savages’ and ‘primitives’. Additionally, anthropologists visiting Swat seemed to focus exclusively on male roles and their influence on Pashtun life, largely because Pashtun society is segregated.

“When I arrived at Cambridge to do my PhD, I really wanted to challenge this perspective. I tried to bring in the missing element – the women’s perspective – as I sought to apply anthropology to my society.”

An old world through new eyes

“My PhD focused on Pashtun women. The Pashtuns [or ‘Pukhtuns’] are one of the biggest tribal groups in the world, with over 14 million people. Pukhtuns are a very diverse tribal group. The Taliban form a small branch of it, and many other tribes and peoples – including the people of Swat – form another.”

While in Pakistan to research her thesis, Amineh found that many social dynamics had been overlooked by preceding anthropologists, who were all male.

“As a woman, I had far more access to the female sections of Pakistani society. I saw an enormous amount of economic activity and monetary exchange among the women. Women managed so many rites of passage: moments of birth, death and marriage all ran through them. Only if you saw it superficially would you think that women had no role here. In reality, women were running the social fabric of society. They managed relationships and money during gham-khadi events [specific segregated gatherings in Pakistan, like funerals and weddings]. I was told that the world is established on the work of gham-khadi, done primarily by women.”

Amineh returned to live amongst Pukhtuns to better observe their behaviour and cultural dynamics. She analysed traditions familiar to her in a new way, made possible by her study of anthropology.

“In Islam, there is an old idea: everyone has two angels guarding them – one sits on your left shoulder, the other on the right. One angel writes down all your good deeds, the other all the bad deeds. While I was conducting participant observation in Pakistan, I would write down everything interesting – conversations, behaviours, routines. I gathered countless notebooks and fieldwork data. One day, an old lady I lived with said to me in Pashto: ‘You’re just like the angels who write down everything!’”

In order to bridge the gap between her academic work and the general public, Amineh has written her latest book, Gems and Jewels. The book aims to be more accessible in style, and includes beautiful artwork to illustrate some difficult, unfamiliar ideas. The book tells the stories of Pakistan’s diverse religious communities (Christians, Hindus, Muslims, Jews, Buddhists, Baha’is, Sikhs, Parsis, Kalasha and Jains), challenging the media’s monolithic view of the country. The book amplifies the voices of those often marginalised – tribal peoples, women, and the young – and investigates how they deal with life’s difficulties.

The approach Amineh uses in Gems and Jewels, which seeks to understand other cultures by using empathy and compassion, was forged in her experience of interfaith dialogue and peacebuilding studies. Cambridge provided the perfect place for Amineh to develop and hone these methods.

A blueprint for world peace

“Cambridge has been a home for me, both literally and intellectually. I did my A levels here and eventually my PhD. I’ve always found life in Cambridge to be a sort of ideal existence, almost utopian.”

“The University has always been a bridge between cultures and continents, the east and the west. Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, a prominent leader of South Asia, founded India’s Aligarh Muslim University after he was inspired by Cambridge, where his son studied.”

“During my time at the University, I’ve seen an immense respect for the diversity of others' opinions. This is something I’ve tried to inspire when working in other parts of the world.”

After she'd finished her PhD at Cambridge, Amineh set up the Centre for Dialogue and Action at her college, Lucy Cavendish. Through this Centre, she sought to foster connections between scholars of different religions and encourage conversations with her students.

Amineh’s first students included women of all ages, as well as rabbis, priests and imams. She tried to find ways of sending them back to their communities with improved knowledge, so that they might build bridges with historically adversarial groups.

“We went on field trips to synagogues and mosques, learning as much as we could about different groups’ value systems. We focused on some core qualities, particularly empathy and respect for others. We found that combining scholarly research with personal encounters with other faiths, where one could directly experience the lives of others, was really important. We built a lot of friendships in doing that.”

For one project at the Centre, Amineh worked with the Mayor of Cambridge to set up an interfaith conference at Cambridge’s Guildhall. She invited high profile guests to join the conversation, including interfaith campaigners, the head of the Muslim Council of Britain, and other heads of religious communities. Amineh even managed to get Prince Hassan of Jordan and Queen Elizabeth II to send messages in support of the conference. It was at this conference that the head of Cambridge’s Woolf Institute saw Amineh in action.

“He came up to my College afterwards to visit me and said he was setting up a world-first centre, and I was just the sort of person he had been looking for. So, after applying and interviewing for the role, I became the first director and co-founder of the Centre for the Study of Muslim-Jewish Relations.”

“I was relatively young when I became Director of the Centre and had to grapple with big questions and issues. While building the Centre, I wanted to continue to develop intellectually. I began to study and learn both Hebrew and Arabic, so that I could better design and teach these new courses. We dealt with students (even senior religious teachers and professors) who came in with mistaken or biased ideas; but by the end of our courses, you could see their mindset change. It’s an enriching and beautiful experience to play a part in that transformation.”

While researching new courses, Amineh met with and studied the work of the late Chief Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks. She found his book The Dignity of Difference particularly enlightening.

“I found his work really inspiring. Particularly his ideas of building interfaith communication by exploring similarities, while at the same time respecting differences. In his ideas, methods and Abrahamic warmth, he felt like a teacher and uncle to me.”

In these experiences, Amineh had hit upon a fruitful approach to peacebuilding studies: an interdisciplinary blend of anthropology, sociology and religious studies. Her next step was to find a way of applying what she’d learnt to other contexts.

Building peace across the world

Amineh soon took the skills and knowledge she’d learnt at Cambridge and set up another centre in Pakistan. Like her first venture at Lucy Cavendish, she named it the Centre for Dialogue and Action, but this time it was situated in one of the oldest universities in South Asia – Forman Christian College in Lahore. But this was also a city in which courses on comparative religion had been banned by local religious leaders. Amineh was treading on difficult ground.

“It proved to be a very interesting course to run. Many of our students joined from remote regions of Pakistan, without knowing what to expect.”

“One student came from North Waziristan, one of the most deprived and bombed places on the planet. Bombs had killed many of his tribal relatives, and drones had traumatised the young people. At the beginning of the course, this young boy said to me that people of other faiths should be killed. I realised that he was from a community without much exposure to other faiths. Rather than being harsh on him, I tried to show compassion, and urged him to finish the course and see if his opinion changed. By the end of the course, this boy, along with a host of other quite upset young men – whose worlds are often in turmoil, and whose restless energy seeks stability – were changed people. He told me that he now wanted to read, to love people, to respect people. That young boy went on to do a PhD. I felt so privileged to be involved in changing mindsets at the forefront of some of the world’s most troubled regions.”

At the new Centre in Pakistan, Amineh replicated other techniques she learnt in Cambridge. She took interfaith groups, consisting of rabbis, priests and scholars, into some of Pakistan’s most deprived areas. Here, she tried to encourage personal encounters with marginalised people.

“We spoke to people living in very small spaces, who counted an Urdu Bible among their only possessions. They were such kind and generous people. It’s here where you really find the best of humanity, not necessarily in palaces and places of opportunity, but in the poorest places in the world. One little Christian Pakistani girl took a rosary she had made by hand and gave it to a member from our group, a priest from New York. He said it was the most moving gift he’d ever received.”

Hope for the future

Amineh’s mission is far from over. She’s recently worked with the United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect, connecting them with Pakistan’s Higher Education Commission to combat hate speech in universities, drawing upon local frameworks of soft and kind speech from the Seerat [Muslim teachings]. More widely, Amineh wants to roll out her peacebuilding courses on a grander scale.

“In the future, I want to spur humanity onto a higher level. How do we tap into our divine spark, and enlighten ourselves? How can we move forward as a world community? I think one way of doing it would be to roll out interdisciplinary peacebuilding courses on a global scale, including voices from all faiths. That way, we can truly instil empathy, understanding and respect.”

“People like me, who’ve had the privilege of education and access to many opportunities, can’t sit back. We have to contribute positively to the world in an urgent manner. As scholars or academics, we must bring respect, love and compassion to the people we study.”

“Unfortunately, the media doesn’t portray the complexity of Muslim societies, which can lead to Islamophobia. In reality, there’s a wide variety of people there, and so many need help. Rather than bombing these deprived communities, we should be building schools and hospitals, and helping the less privileged of our human family. Think of the impact that would have for future generations.”

“Today, young people from minority communities in the UK and elsewhere face extreme pressure because of discrimination and the demonisation of their communities. I would love to see a world inspired by the ideals of places like Cambridge, in which we pursue knowledge to the highest level of excellence, while cultivating notions of compassion, justice, kindness and empathy.”